Author: Osman Zukić | Photo: Almir Kljuno

We left the dawn and frost on the Romanija mountain behind. We turned right in Han Pijesak towards Rogatica and Žepa, and continued further to where Google Maps were taking us. As we cut deeper into the mountains, there were fewer cars along the way. Only a sporadic piece of heavy machinery, a rusty truck, and wild animals on the road. The evergreeen forest is getting denser as we reach higher altitudes.

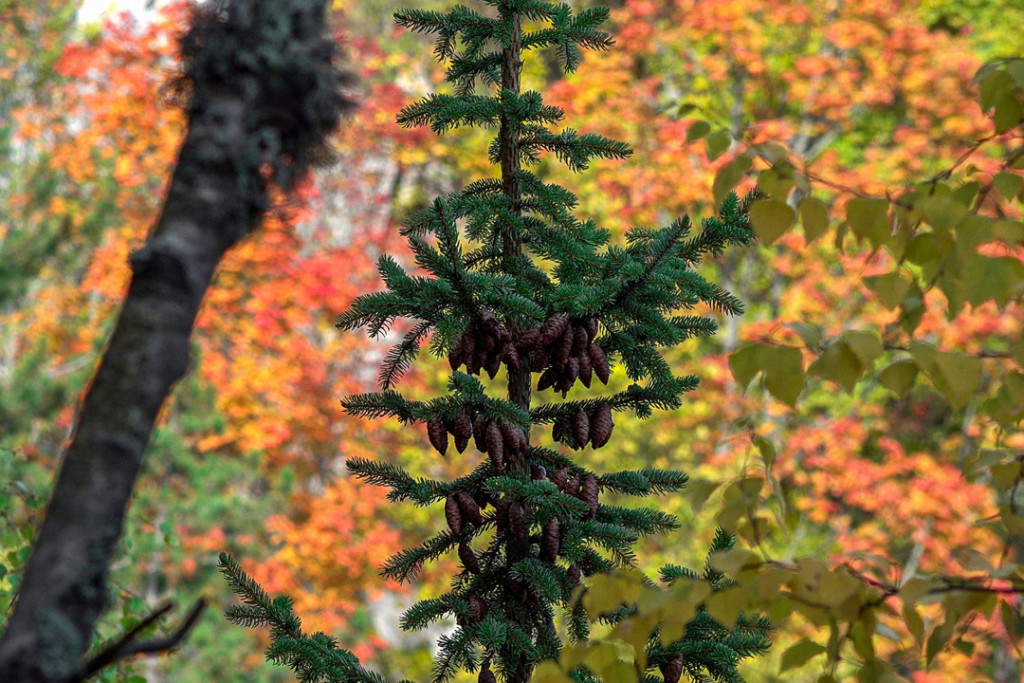

You look from one mountain to another, it seems as if the birch, beech, and oak trees, whose leaves are already red, yellow, and brown, are brushstrokes painted by an expressionist. The basin is filled with mist, and it feels like you could step into it. The sky is blue and clear, there are only traces left by airplanes, like straight lines drawn with chalk.

Affectionately called – the sprucie

Ibro Mujić is waiting for us at the fork in the road above his house in his hometown of Luka. He is our guide, and we will also be staying at his place.

The Drina River is not far away. Fog descended again, it’s thick like dough and there's little chance it will rise any time soon. Ibro takes us along a forest path. Machinery can be heard in the distance; we are walking towards the regular rhythm of a tree marking gauge; Ibro is talking. This is the third year he is working as a guide in the Drina National Park. He still doesn’t know whether he will be employed full time. He says that there is little chance of getting a job if you are not on friendly terms with those in politics, it doesn’t mean a thing that you want to work and that you love the forest and nature.

The logging crew come out on the road. They greet us and introduce themselves. Dušan Kovačević is the manager of the protection, development, and the exploitation of natural resources sector in the Drina National Park. They are marking trees for sanitary felling, which is part of regular activities to clean the area of dead and diseased trees, which are a danger to the healthy trees. Serbian (Pančic’s) spruce is the main attraction of this park, and the areas where it grows are zones of primary protection.

It's steep; we hold on to branches and rocks as we descend into the bowels of the forest. Ibro talks about the activities he is in charge of. He takes hikers on tours, receives experts and scholars, and takes them to locations that are of interest to them, clears trails and visits various locations in order to monitor possible threats to the eco-system. He says that all activities are prohibited here, from hunting to tree felling. The only allowed activities pertain to the protection of the forest and development of tourist and scientific and research potentials. He shows us a thin, slender, tall tree whose tops are knitted into the fog.

This is the Serbian spruce (Pančić’s spruce – Picea omorika), or as he affectionately calls it – the sprucie.

Josif Pančić had spent ten years walking through unexplored areas along the lower and middle course of the Drina River before he discovered it. Villagers put him up for the night and fed him. They would bring him twigs and leaves and he would put them in his herbarium.

When he finally discovered it and took it to Vienna - the ice beauty - as he wrote down in his journal - there was no longer any disagreement among scientists as to which was the most beautiful European conifer, nor was there any doubt as to whether it was an endemic species. Later, genetic tests proved that Serbian spruce (picea omorika), discovered in 1877 - is up to sixty-five million years old, and it’s only natural habitats are here - in eastern Bosnia and south-western Serbia.

Pančić asked his students to bury him in a coffin made from his spruce.

No forest order

There are about seventy mother trees, adult and healthy trees in Strugovi, and the natural regeneration looks good. Each tree was marked with a number and entered in the records. It was done by experts from competent institutions and the faculty of forestry professors from Sarajevo and Banja Luka. Ibro took them from tree to tree. We recorded, he says, all the trees we could reach. You’d have to use ropes to reach others. The goal of this process was to record the number of trees and determine the health of this relic from the Tertiary epoch.

The local population used to cut down this endemic conifer species, made boats out of it and built it into their houses. They thought that it was a sacred tree, that it would bring them luck, prosperity, rid them of evil and keep bad luck away from their properties and livestock.

Ibro has seen it all. In the forest, he says, there is no forest order. It all boils down to felling the tree and hauling it away, without worrying about anything else. Tractors and logging trucks are destroying the forest, he claims. In order to extract a log of five to six cubic meters, a dozen young trees are destroyed. First class timber is chopped into firewood; it’s a godawful waste, he says.

The village of Luka and most of the private properties are part of the park, which is divided into three zones - the first in which no activities are allowed, the second where sanitary logging is permitted and the third, which also includes private properties, where any normal activities that are in compliance with the law can be carried out.

After two hours spent in the gorge, we returned to the Borove Ravni plateau. The sky is clearing up. Through the crowns of tall conifers the sun is shining as if through a stained glass of a cathedral window, and as the fog disappears, new colours emerge. The light refracts on the dewdrops, a spider has stretched its web from one tree to another and sways weaving it. Before, it had seemed that there was no sun at all, that it would not come out ever again, and that frost was everywhere. Hence such an intense feeling of warmth and relief.

Experts v. politics

Dušan has been working in these forests for over forty years. In the 1980s, he participated in the creation of the forest management foundations for this area. At that time, it had the highest quality forest in the region, but the market demands, and the development of the wood industry meant that the number of trees to be fell annually proposed by experts was increased due to political pressure.

Just the plywood factory from Zvornik required 20 thousand cubic meters of timber per year.

Forest specialists say that balance between production, growth and yield must be ensured. You take from the forest just what you need, no more. If, for example, ten trees are ready for felling, you cut down six, not twelve.

“After the war, he continues, the forest was not needed so much for trade or wood industry. Instead, it was given away as a compensation for war damages. It was given to veterans, the disabled, and even the civilians who provided help to the army during the war. "There is no bank, no dividend, no interest that can turn money around like forests. If it is managed and cared for properly, it’s better than any bank. And also, there are other benefits - ecological, biological, health, scientific, cultural."

The forest is precious, and everyone knew it then, and they know it now.

“There are forests in our country, explains Dušan, but we don't have the quality, the trees are still young and need to be preserved." I won't be alive, but someone else will be, some future generations will need it. We cannot cut down what belongs to our children, our future generations. We don't need to look for anything more beautiful and better, but to preserve what we have. Public enterprises are political parties’ spoils. There is a lot of irresponsibility, nepotism. It’s not about the market, logic, science, but about parties and politics. We who take care about forests feel trapped, as if in a cage."

Dušan has spent “a million” nights in the forest. He appreciates people who are good at what they do, appreciates engineers who put on their boots and spend the whole day in the field. He says that today employees of forest estates want to protect the forest from their offices. He’s against that approach.

The Austrian travel writer and archaeologist Felix Kanitz wrote in his travel journals that the Pančić’s spruce was used by the Romans to prop up pit roofs in Bosnia. Regardless of the fact that today it is not cut down and that it has been consistently protected for years, that we still study how and under what conditions saplings can be best transplanted, this species is more endangered than ever.

In recent years, it has been noticed that the trees are dying at a more frequent rate, which is assigned to the increase in average temperatures. The explanation lies in its shallow, saucer-shaped root, which cannot absorb as much water as it needs from the deeper soil layers, so it feeds on water from the trunk and branches and thus kills itself.

Apart from that, the last remaining trees of this endemic species are disappearing in fires caused by people. He remembers this summer's fire in the immediate vicinity on Veliki Stolac. More than half of Pančić's spruce habitat burned down then. The inaccessible terrain, the lack of timely reaction, in addition to the absence of fire escape paths made extinguishing the fire extremely difficult. The fire was put out by groundskeepers, local population, and a helicopter that subsequently joined in the efforts.

Dušan does not believe that fate is to blame for the accident, although that’s what people like to say. Fate cannot be blamed, he says, we should make as few mistakes as possible, as mistakes are the cause of all disasters and misfortunes.

Here they have at their disposal an old Lada, some hand tools, backpacks with manual fire extinguishers and people ready to put out fires when needed. These areas are about fifty kilometres away from Srebrenica, the road is bad, communication is slow and by the time help arrives, he says, the fire will have spread. That’s why it’s important that people are careful what they do and where, especially in the spring when they clear the fields and burn the debris.

We have no back-up countries

Pančić's spruce also grows in the Grad and Šarena Bukva locations. The trees are younger, there are fewer of them, and it is difficult to reach them, but they are a fairly healthy. Ibro will take us to see them. Since we cannot go by car, we will climb for an hour and a half to get there. We also pass through his property; he shows us the log cabin that he plans to renovate. The shads in which cattle used to be kept, and those in which shepherds slept, are overgrown with vines, ferns, hawthorns and bramble. Only the path that our guide occasionally uses to lead groups of hikers can be seen. Today, the fields are overgrown with undergrowth. There are no people to cultivate them, and the fields where cattle and sheep used to graze have become overgrown.

It's the best feeling when you don't know what you're going to see climbing up towards the mountain cliff top. You will see the deeply cut canyon of the Drina River. The light coming from the west hits its right bank, it is full of colours and you can clearly see all the shades of autumn. The west side is dark, just like the river. Ibro shows where hiking trails are marked and where more of them will be marked. Had leaves had fallen off the trees, it would also be possible to spot the Alpine chamois.

While slicing smoked sausages and home-made bread, Ibro says that if he doesn't get a full time job, he will farm cattle or go to Ilijaš. He will find a job, he says, but he would rather spend his days here. He daydreams that one day there will be tents here where hikers can spend the night, be offered cheese and clotted cream, homemade flat bread, pies, and fritters.

From the cliff top we see the slender trees of Pančić's spruce. They had found themselves a place here and have been here for millions of years. Their pyramidal crowns and the colour of the needles, which changes from dark green to silver in the light, are considerably different compared to pine, spruce, or fir. Once you see it, you will always recognize it, no matter how hidden it is among other trees. We descend even deeper towards the canyon. Reaching the rocks, we can see more clearly the trees that have died. Here, they are left to their own devices.

The Sun is dipping towards the west. The shadows of the trees are getting longer and if you watch closely you will see them disappearing on the other bank. Ibro’s mother and two older brothers meet us at his house. The room in which we will sleep is warm, and beech firewood is piled up next to the stove. The fire blazes and its glinting reflection bounces off the walls. They say that the winters here are harsh, and the snow can come early.

The morning dawned bright and clear. Such a morning that makes you think that yesterday was just an illusion, a dream in which, according to some perfect logic, so many steps, thoughts, words, messages and information took place, and that today a story is born. Šarena Bukva is another location we will visit. There are even fewer trees of Pančić's spruce here and the slender trees sway in the strong wind. We say goodbye to Ibro. If they don't give him a full-time job, I say to him, they won't give it to someone who knows these grounds like the back of their hand and who speaks so beautifully about the landscapes, vantage points, trails, plant and animal life that is so diverse in this region.

Heavy machinery prepares the dirt road for asphalting. For the longest time, there have been rumours among people that the road is not built to every house in the village because of those who live in those houses, but because it is easier for politicians to reach their constituency before the elections. And the elections are next year. Ahead of elections no one talks about how to preserve our forests, and no one asks for whom the trees grow with people leaving the country every day, but instead they are looking for a way to manage them longer and exploit them faster, at any cost.

In his book The Hidden Life of Trees Peter Wohlleben writes that trees have memories, exchange messages, feel pain and get sunburned. That they even get wrinkles. He writes about how modern forestry actually produces wood - it cuts down trees and then plants new seedlings - and the interest in the well-being of the forest exists only to the extent that it is necessary for the optimum management of the forestry company.

On our way back, we pass trucks carrying asphalt. We're leaving. From now on, whenever I walk through our forests hiding in their depths the most beautiful European conifer, I will remember Dušan’s words. We don't have a spare country, we don't have a spare planet; we don't need to look for anything better or more beautiful, just protect what we have. Future generations will thank us.